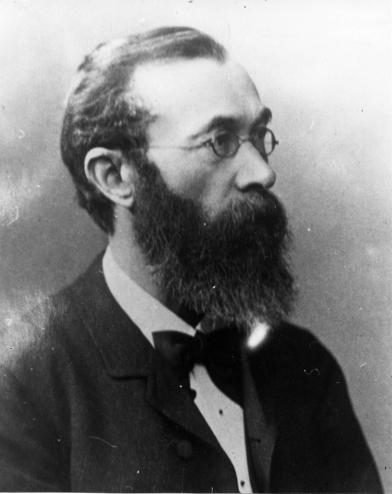

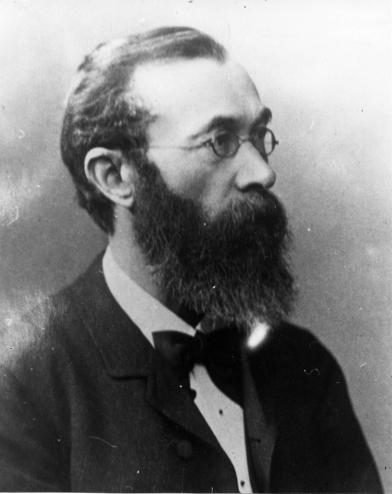

When I went over who Wilhem Wundt was with my psychology students yesterday – “the father of psychology” – I was struck by our text’s manner of introducing him as just another brilliant mind who floundered in school:

“Like many famous people, he (Wundt) got off to a rocky start. Darwin’s father, for example, had called his son a bum and told him he was too lazy and stupid to ever amount to anything. Albert Einstein, one of the world’s greatest mathematicians, kept failing high school math and failing college entrance exams. When he finally got through school, he said it had injured his mind. So, too, with Wundt: he had spent most of his time daydreaming and failing, for his teachers kept slapping him in the face (literally).”

“Like many famous people, he (Wundt) got off to a rocky start. Darwin’s father, for example, had called his son a bum and told him he was too lazy and stupid to ever amount to anything. Albert Einstein, one of the world’s greatest mathematicians, kept failing high school math and failing college entrance exams. When he finally got through school, he said it had injured his mind. So, too, with Wundt: he had spent most of his time daydreaming and failing, for his teachers kept slapping him in the face (literally).”

To be honest, I automatically agreed with this statement as I went over it. How could you not? School is no place for brilliant, deviant, field-creating thinkers, right? How could it be? The mission of schools is to teach students about fields of knowledge that already exist, right? You couldn’t have a course titled, “Create a New School of Thought 12,” offered in the course calendar, could you? What would the prerequisites be? A track record of frustrating and annoying teachers? Daydreaming? What would its standards and benchmarks be? How could you blanket what a good school of thought was versus a bad one? Now that would be tricky!

Then I looked up at my students. They were just sitting there, patiently waiting in silence (I must have been staring into my textbook for a good while), and I asked myself: Do they need to flounder in school in order to be game-changers? How many Darwins, Wundts, and Einsteins have I taught? How many of my students have had the genius beaten out of them by red x’s, teacher sighs and eye-rolls, pre-packaged content, and standards and benchmarks that challenged them to ‘get’ what has already been discovered by others? How can I, with my prescribed curriculum, challenge them to discovering things for themselves? Are schools, then, worthless? Should I just stop the lesson and tell my students the dirty little secret that the author of this text is referring to?

I wish I could have seen the look on my face when I read the next sentence from the text:

“Fortunately, a few teachers saw the promise of greater things in him (Wundt) and helped him to pull himself together.”

“Aaah,” I thought, “That’s why we’re here.” And with that bit of paradoxical irony, I continued on with the lesson.

* * *

End Note: (and I’m not joking) After class a student (who a colleague of mine referred to as the boy “With a lot of stuff going on in his head,”) came to my desk and asked if I had ever read Julian Jaynes’ The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown in the Bicameral Mind. Ironically I had. I couldn’t believe it!  That book was/is the most mind-blowing, field-converging book I have ever read. I was 24 when I read it and it took me a long time to get through it. This student is 16 and I got the sense that he read it over a weekend. We talked for some time and he ended by saying how one of his goals in life is to learn lots about a lot of different things so he can create his own insightful conclusions and associations … just like Julian Jaynes (and Darwin, Wundt, and Einstein if I might add). It was a perfect way to end the class.

That book was/is the most mind-blowing, field-converging book I have ever read. I was 24 when I read it and it took me a long time to get through it. This student is 16 and I got the sense that he read it over a weekend. We talked for some time and he ended by saying how one of his goals in life is to learn lots about a lot of different things so he can create his own insightful conclusions and associations … just like Julian Jaynes (and Darwin, Wundt, and Einstein if I might add). It was a perfect way to end the class.